Fox Vulpes vulpes

Fox Vulpes vulpes

- Red Fox

- Silver Fox

- Inheritance of red, gold, and cross fox

- Gold Fox/Smoky Red

- Cross Fox

- Mutants

Grey Fox Vulpes cineroargenteus (Eastern Grey Fox)

Arctic Fox Alopex lagopus

- Blue

- White Fox (Polar Fox)

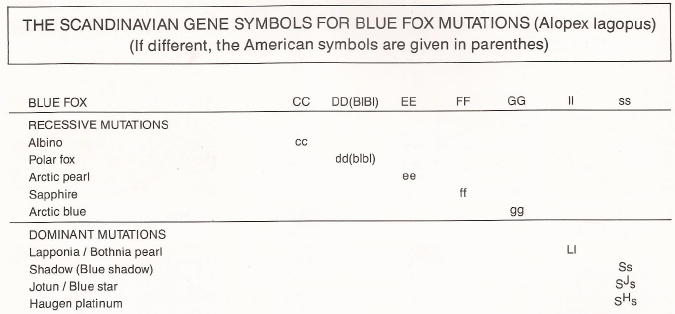

- Mutants

Mutant Color Phases

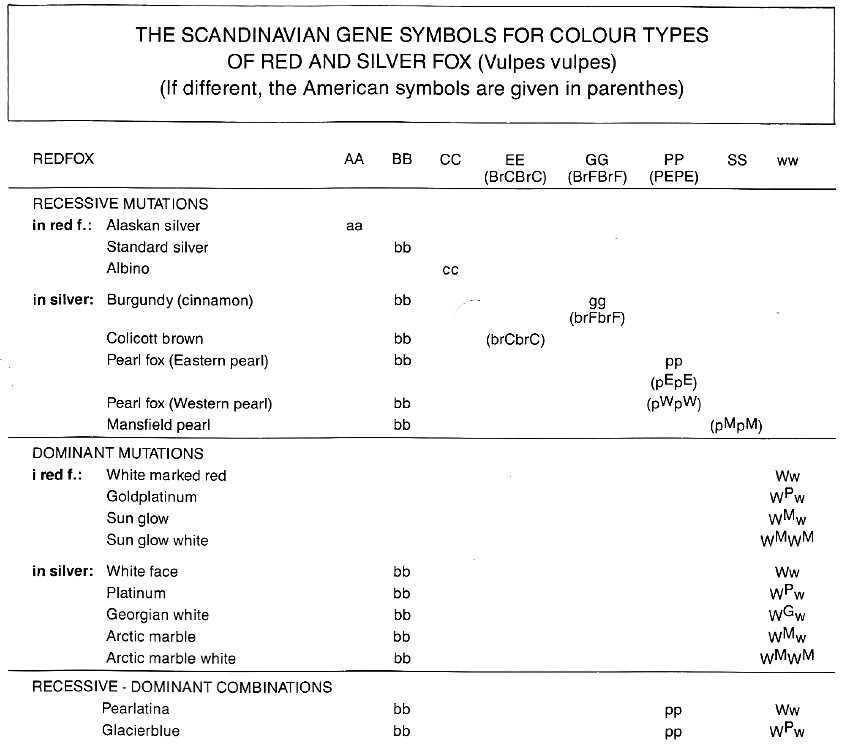

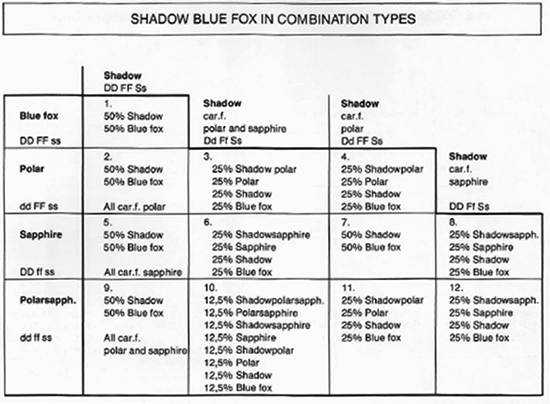

Table 1

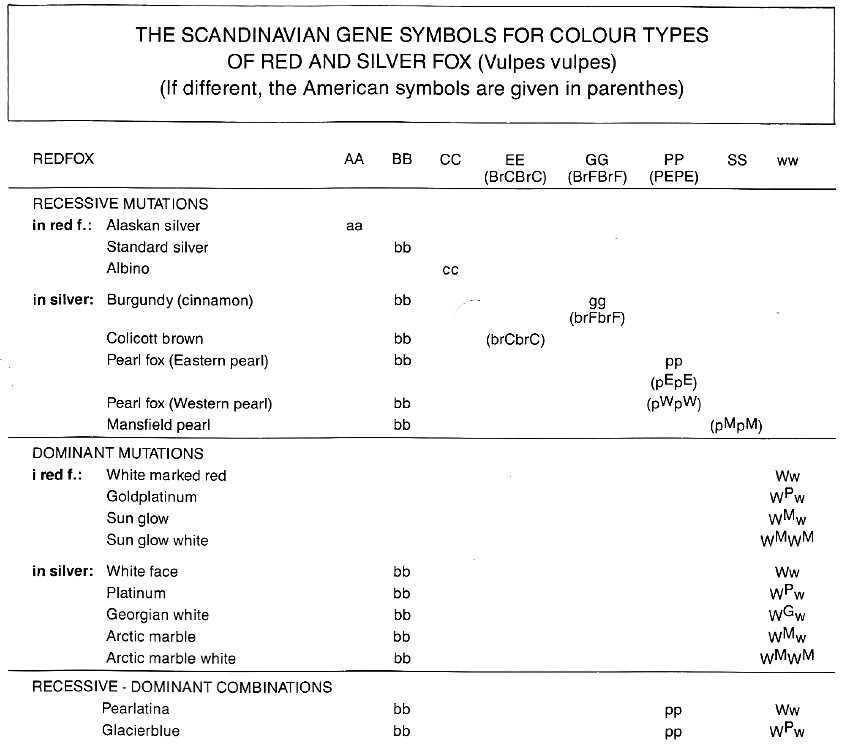

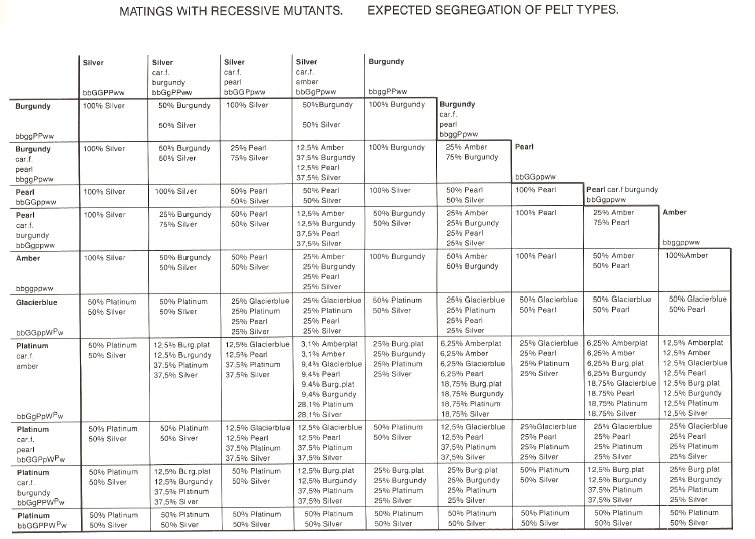

The official Scandinavian system of gene symbols covers the color mutations of red and silver fox presented in the table above. This list of genotypes was officially accepted by the Fur Animal Division of the Scandinavian Association of Agricultural Scientists in 1981 but since then new color types have been imported to Scandinavia and even born here.

Among the new types is e.g. another brown mutation of silver fox, which in USA is called Colicott Brown (picture 17). the type itself is lighter in color than burgundy but reacts in similar way in combinations. For example a combination of colicott and pearl produces a light brown color resembling amber (picture 23).

In regard to some of the new color types the information about their genetic back ground is not yet quite confirmed. As soon as the additional information is obtained by breeding trials the gene symbols for them will be added to the Scandinavian system.

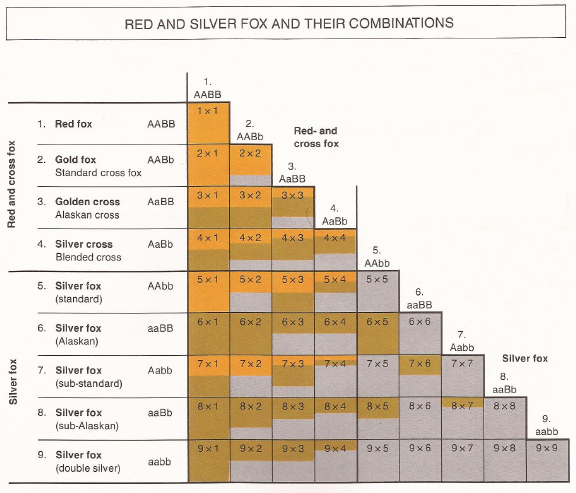

Red fox – Cross fox – Silver fox

When using silver fox in combination types we all time have to be aware of the fact, that all silver foxes are not genetically alike. Because the Alaskan type and the Standard type have long been mixed, the Scandinavian silver fox population today consists of 5 different genotypes (page 2 types nr. 5 to 9). Therefore all mutation types of silver fox also can exist in 5 different genotypes even though they in the table of gene symbols are only referred to as mutations in standard silver.

Neither is it possible by judging the phenotype to determine, which black genes there are involved, as long as one of then is in homozygous form (either Aa or Bb) they, however, have a different color effect. therefore the three genetically different forms of cross fox to some degree can even phenotypically be distinguished. The poly genes affecting the shade an intensity of the color, however, cause additional variation and overlapping forms even in the cross-types.

Cross fox genotype: Standard cross fox AA Bb (picture 1) Marketing name: Goldfox

Cross fox genotype: Alaskan cross fox Aa BB (picture 2) Marketing name: Golden cross fox

Cross fox genotype: Blended cross fox Aa Bb (picture 3) Marketing name: Silver cross fox

1. Gold fox

2. Golden cross

3. Silver cross

As mentioned before, the poly genes for color intensity can make some Alaskan cross foxes so dark that they are sold as silver cross fox. For the same reason some blended cross types can be sold as silvers. All cross types are also found among wild foxes in Scandinavia. As a matter of fact, most of the wild red foxes represent genetically the standard cross type.

In speaking about the cross ties we also must remember the large variation in the color of the red fox from dark brownish red to light yellowish shade. Whether this variation only is due to the poly genes and what is the role of the different shades of color in the production of cross types has so far not been investigated.

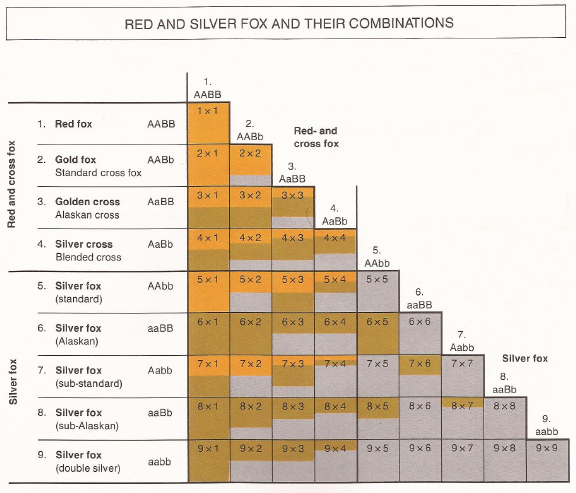

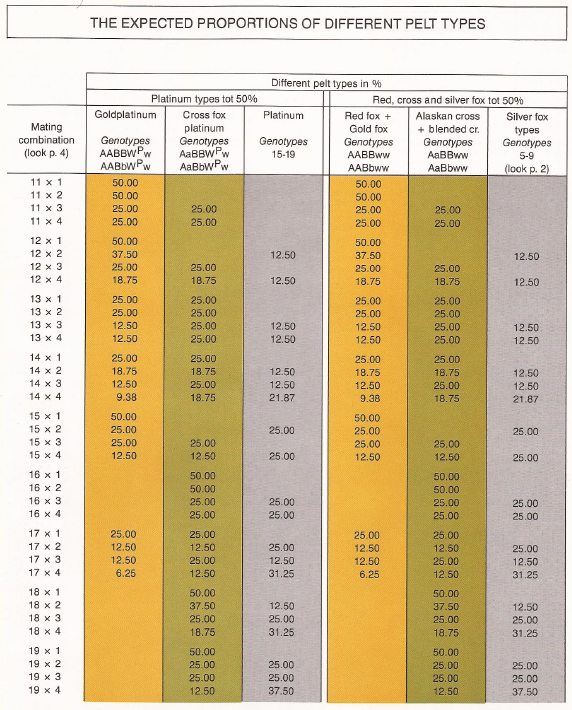

Table 2

Because of the different possibilities regarding the genotype, the matings between red fox, cross fox and silver fox types can produce red, cross of silver offspring in varying proportions. In the above table the genotypes AA BB (red fox) and AA Bb (standard cross fox = gold fox) are marked with the orange color, the genotypes Aa BB (Alaskan cross) and Aa Bb (blended cross) with the brown color and all silver types with the grey color. In most cases the proportions of different pelt types are 25, 50, 75, or 100 percent.

4. Gold fox

5. Light silver cross

6. Silver fox and dark silver cross

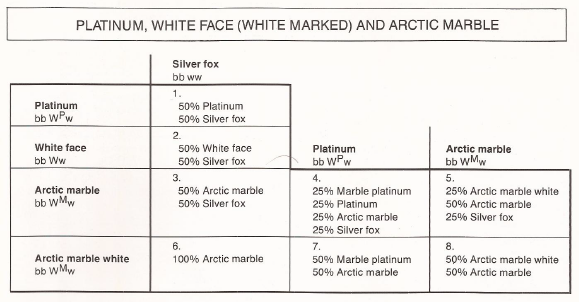

Table 3

As it is impossible on basis of the appearance to reveal the genotype of silver fox, the matings with red fox or standard cross fox or inter species crossing with polar fox can be used to get evidence of the genes involved. The fact, that we sometimes in pure silver x silver matings get blended cross offspring (picture 6) is, however, a clear proof of the existence of genetically different silvers in our farm populations. That this occurs fairly seldom is understandable, because obviously the types 7, 8 and 9 now have become more common. Even if we assume that ll five genotypes would be represented in even numbers, the possibility of getting something else other than silvers is only 15% (see table on page 2), and in these cases the result always is a blended cross.

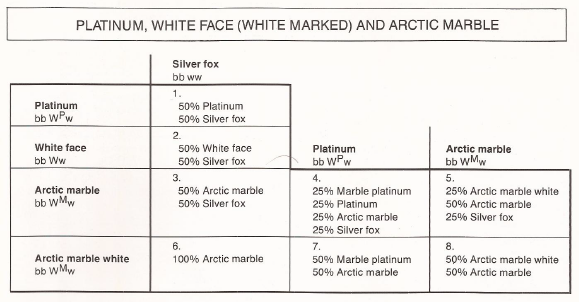

Of the gene w a series of several allelic forms is known. The darkest color is the white face (white marked) (picture 7), and the lightest the Georgian white (this, however, is known to us only from Russian reports). White face and platinum genes in double dose (in homozygous condition) are lethal. According to Russian reports homozygous Georgian white have been born.

Because of the lethal factor, the matings of platinum x platinum, platinum x white face or white face x white face are not to be recommended. In these cases 25% of the fertilized ova are unable to live.

The most common go these alleles is platinum. The variation in the color (picture 8) is partly due to the poly genes and partly to the genetic types of the silver fox. The white collar, however is always more district than in the white face type.

For arctic marble type has previously been used the symbol M (picture 9). No lethal factor is connected to this type and therefore it can be produced even in homozygous condition. HT homozygous individuals are almost white with black ear edges (picture 10).

A combination of arctic marble and platinum will also be almost white. It has been proved that marble gene and platinum gene are allelic (marble is undoubtedly similar to the Russian Georgian white). The gene symbol will therefore be changed to WM.

Matings of marble platinum with the original types will produce the following offspring:

Marble platinum x silver fox:

- 50% arctic marble

- 50% platinum

Marble platinum x arctic marble:

- 25% marble platinum

- 25% arctic marble white

- 25% arctic marble

- 25% platinum

7. White face (light)

8. Platinum (light -dark)

9. Arctic marble pups in August

10. Silver fox and marble white

Because of the lethal factor in platinum, the mating marble platinum x platinum is not to be recommended.

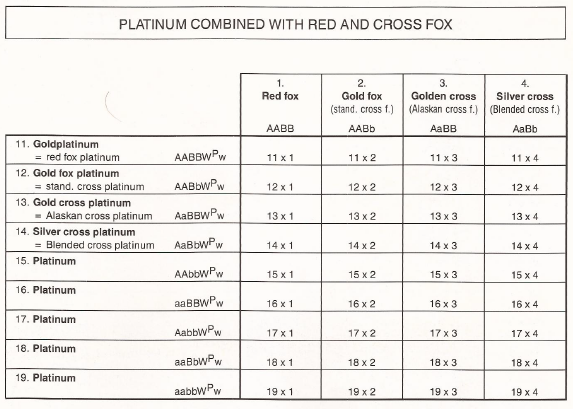

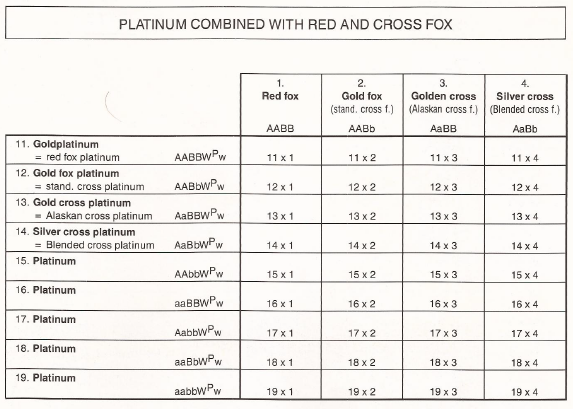

Table 4

All mutation genes originally born in silver fox, can be transmitted to the red fox or the cross types. The dominant genes produce the same pattern of white areas as in the silvers, but the black color is partly or completely replaced with red (picture 15).

In combinations with the recessive mutant genes the red color usually is dominant to that extent, that if the black genes (a or b) are not present the mutant color only can be seem on the legs and behind the ears (pictures 24).

In pictures nr. 11 to 15 are presented some results of combining platinum or arctic marble gene with red fox or various types of cross fox. In these cases the combinations with blended cross fox, sometimes even the ones with Alaskan cross fox, easily can be mixed with respective types in silver fox. On the other hand the combinations with gold fox resemble the respective combinations with red fox and are sold as gold platinum or sun glow. Only the slightly darker tail (picture 13) can reveal that the type is a carrier for standard silver.

11. Goldplatinum

12. Gold fox platinum

13. Goldplatinum (of gold fox)

14. Sun glow and sun glow white

15. Skin colors from sun glow to arctic marble

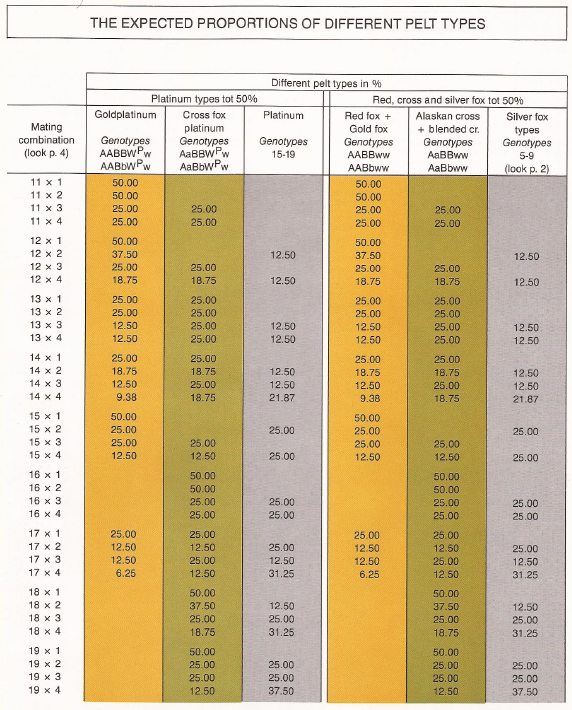

Table 5

Using the Tables 4 and 5 one can find out the proportions of pelt types expected from different matings. (In the brown group both Alaskan cross (golden cross) and blended cross (silver cross) types are included). The tables can as well be used to illustrate the combinations with arctic marble factor by replacing the platinum gene WP with arctic marble gene WM. In the pelt types the orange color represents sun glow types (AA BB WMW and AA Ab WMW, the brown color cross marble types (AaBB-WMW and AaBbWMW) and the grey color arctic marble types (all silver fox types with arctic marble factor WMW). If instead of heterozygous arctic marble the homozygous arctic marble white is used in these combination there will be no red, cross or silver types but the proportions of different marble types will be doubled.

The Recessive Mutants of Silver Fox

The recessive colour mutants of silver fox have been more unknown in Scandinavia until quite a few of them recently have been imported from USA, Canada and Holland. As known from the Mendel’s laws of heredity, in these cases the colour gene has to be inherited form both parents before the effect can be seen in the phenotype. In regard to the phenotypes (the appearance) some special characteristics have to be remembered:

1. If the mutation type is produced in silver fox, we have to remember that because of the silver colour already one or two recessive genes (aa or bb) are involved. The possible variation in silver genotypes obviously adds the variation of shade and intensity of the colour from what normally is caused by polygenes. The silver fox in USA and Canada is claimed to be pure standard silver, but obviously also the Alaskan gene at least to some extent is present.

2. In single recessive types combined with red fox (AA BB) or gold fox (AA Bb) the mutation colour usually can be seen only on the areas, that normally are dark e.g. on the legs and ears (picture 24 and 25). After this breeding season we hope to be able to describe also how these genes react in Alaskan cross and blended cross types.

3. All recessive genes need not to be completely recessive. Especially when several genes are involved (as in question of recessive mutants in silver fox) some genes can already in heterozygous form (e.g. Pp) change the colour to some extent. We often discover that platinum or silver being carrier for pearl is somewhat lighter and softer in the colour than pure platinum or silver.

16. Burgandy = Cinnamon

17. Colicott brown

18. Amber (Burgandy + Pearl)

19. Pearl

20. Pearl (Mansfield pearl)

21. Sapphire (Pearl + Pearl)

22. Glacier blue (Platinum + Pearl)

23. Fawn Glow

And Their Cominations

Albino red fox

An albino mutant of red fox has been discovered the first time already in 1938. As characteristic for albinism in general, the animal is totally lacking pigment (picture 26). So far, no evidence is available of the effect of the gene in heterozygous form or in combinations with other genes.

Brown mutants

At least two genetically different brown types are known. The darker one, burgundy (picture 16), is obviously more common. In connection to this colour also names cinnamon and Fromm Brown are used , but regarding the genotype they refer to the same mutant. Burgundy combined with red fox or standard cross fox gives a red type with brown legs, cinnamon gold (picture 24).

The other brown mutant, colicott brown (picture 17) seems to be slightly lighter and more greyish brown but normal variation of the shade obviously occurs. The eyes are bluish grey compared to the brown or yellow eyes of burgundy.

Two other brown mutations are reported, the Scandinavian pastel fox and a Polish dark brown mutation but whether they are the same or allelic to burgundy or colicott has not been investigated.

24. Cinnamon gold

25. Red pearl

26. Albino red fox

27. Dawn glow (Bollert’s brown + Pearl)

28. F2 generation after mating dawn x amber

29. Amber sapphire, sapphire and Amber

Table 8

Grey mutants = pearl types

Pearl types are grey mutants of silver fox (pictures 19 and 20). In the American information we again find several different names of pearl types (eastern pearl, western pearl, Pavek pearl, Cherry pearl, etc.). However, at the moment nobody seems to be quite certain about how many of these types are genetically different. It is possible that the same mutations has occurred several times or that in some cases it is a question of allelic forms of the same gene. Eastern pearl and western pearl have earlier been described as different genetic types. Dr. Shackelford means, however, that according to the latest information from farmers it is possible that the types are allelic.

A pearl type which is proved to be genetically different from eastern and western pearl, in Mansfield pearl (picture 20). When first discovered it was claimed to be brownish grey compared to the other types. Selection for the color can have eliminated this difference, but a blood test reveals a low coagulation rate typical for this type.

This genetics of the pearl types is one of the open questions regarding fox color genetics. because of the important role of the pearls in some combinations, it is necessary to get it investigated as soon as possible. With the help of the fox farmers in Scandinavia, USA, and Canada we hope to be able to get more information already next year.

Pearl genes combined with red fox or gold fox produce a red for type with grey legs, grey-red fur and ears (picture 25). In gold fox the type is called Dakota gold.

Recessive combination types

A general rule is, that a combination of a brown mutant and a pearl mutant produces different phases of light brown color.

A combination of burgundy and pearl is called amber (picture 18) and respectively colicott brown + pearl fawn glow (picture 23). What the use of different pearl types probably means for the color of these combinations is so far not investigated, but it is possible that the effect of different pearl factors falls within the limits of variation caused by polygenes for color intensity. To this series of light brown mutations belong also a color phase called snow dawn.

A brown mutant, Bollert’s Brown, is known from the Bollerts‘ fur ranch in Canada. Its relation to the two previously described types is not completely clear. This mutant combined with a pearl type is called Dawn glow (picture 27). (The present dawn glow population is, however, fairly light in color, which indicated that probably three genes might be involved)/ According to information from the owner, a mating between dawn glow and amber only gives silvers in the first generation. This inclines that both the brown and the pearl factors in these two types are different. These silvers would in that case be heterozygous for 4 mutant genes. Mating these silvers together can therefore produce several new combinations and colors (picture 28).

From mink farming we know that a combination of two grey mutants, aleutian and silver-blue, produces a blue type, sapphire. A similar result in silver fox production is achieved by combining two pearl types (picture 21). Even though we are not sure about how many genetically different pearl mutants there are, it is fairly certain that always, as two pearl genes, existing in different chromosomes, both are in homozygous conditions in a silver fox, a sapphire colored type is produced.

Even some triple recessive phases of silver are known, the sapphire amber in picture 29 (to the left) is a combination of burgundy and two different pearl types.

Dominant – recessive combinations

We also have some examples of the dominant types combined with recessive colors. In these combinations the dominant factor again lays down the pattern and the homozygous recessive phase the color of the pigmented areas.

A combination of platinum and pearl is called glacier blue (picture 22). White face with pearl gives a darker type, which in older literature is called pearlatina.

In Table 8 the combinations of brown color phases and platinum are called burgandyplatinum (bb gg PP WPW) and amber platinum (bb gg pp WPW). The arctic marble factor can respectively be used to produce burgundy-marble (bb gg PP WMW), amber marble (bbgg pp WMW), pearl marble (bb BB pp WMW) and eventually sapphire marble.

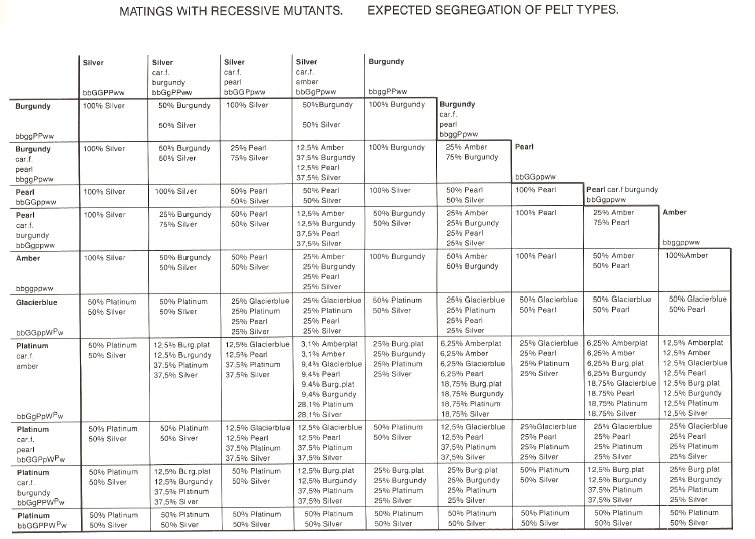

Segregation Table 8

Table 8 describes the expected segregation of different pelt colors in some mating combinations. The description of the genotypes is not included. In further breeding, however, even the genes in heterozygous condition have to be considered.

In many cases it is possible to figure out the genotype of the offspring with certainty if we remember the following rules:

- A dominant gene always can be detected by the phenotype, For example if the offspring after a platinum or glacier blue has a platinum pattern, the genotype according to this mutant gene is WPw, and if it si without platinum patter the genotype is ww. In other words WP gene cannot be concealed in the genotype with our having an effect on the appearance of the animal.

- The recessive factor effects the phenotype only when inherited from both parents (in homozygous condition). A burgundy colored fox has the gene g in homozygous condition (gg). Therefore the color factors indicated in the name of the offspring type always are in homozygous condition.

In regard to the recessive factors, which cannot be seen in the phenotype of the offspring, one can only be sure that the genes exhibited in homozygous form in one of the parents, always exist in heterozygous form in the offspring. For example in a mating amber (bb gg pp) x burgundy (bb gg PP) even though the offspring are burgundy colored we know that they are carriers for pearl (bb ggPp).

As an example of how to use the table we can try to find out the fastest easy to increase amber color as starting from amber males and silver females:

Mating or insemination: amber x silver

Offspring in the first generation: 100% silver

We know, however, that these silvers are carriers for both burgundy and pearl (bb Bg Pp).

Mating or insemination:

amber x silver (carrier for amber, bb Gg Pp)

Offspring in the second generation: 25% amber, 25% burgundy 25% pearl, 25% silver

As the amber male is homozygous for both burgundy and pearl we again know, that all offspring must be at least heterozygous for these genes. This means that the burgundy cubs are carriers for burgundy (bb Gg pp) and the silver cubs carriers for both genes (bb Gg PP).

New Colors from the USA

In pictures 30-36 presents a series of color types which have caused a great deal of discussion in Scandinavia during the last year. The pictures are taken in connection to the Madison Fox Show in October 1984.

Here again we at the moment are not able to give a definite description of the genotype. The present theory, based on information from USA, is that we are dealing with a factor that affects the shade of the red color. It reacts already in heterozygous condition (semi-recessive or semi-dominant).

Whether this factor is related with or linked to any of the previously known mutant genes is not yet completely clear. It seems not to be able to change the color of silver fox or types where genes aa or bb are in homozygous condition.

The factor is in USA called either fire factor or Ph-factor. It seems to interact with recessive genes such as e.g. pearl making the red color in red and cross pearls extremely pale red or yellow. The factor has in the United States been combined with red fox and various types of cross fox and respective pearl, amber and fawn glow types.

According to this theory the color types on this page are:

30. Wildfire = red fox with fire factor

31. Moon glow = blended cross pearl with fire factor

33. Golden sunrise = gold fox with fire factor

34. Snow glow = fawn glow on cross fox with fire

35. Golden cross fire

36. Autumn fire = amber + fire

30. Wild fire

31. Moon glow

32. Fire & ice, dark

33. Golden sunrise

34. Snow glow

35. Golden cross fire

36. Autumn fire

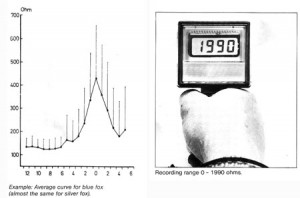

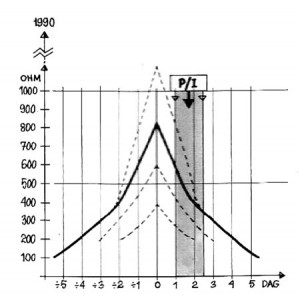

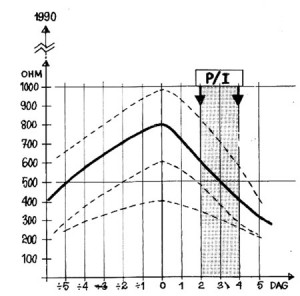

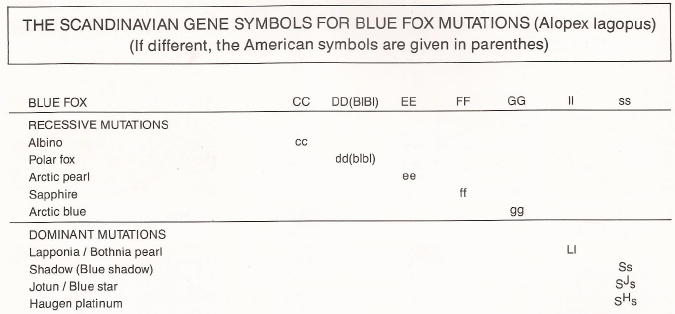

Table 11

In the early beginning of blue fox farming, two types of blue fox war introduced to the farms, the Alaskan blue fox and the Greenland type blue fox. They are referred to as local strains differing in the type of hair and fertility. A remarkable difference in the color was also evident and it is not completely out of the question that they may have been two different allelic color phases. Our present blue fox (picture 37) resembles the Greenland type, but on some farms exceptionally dark individuals like the old Alaskan type can occasionally occur.

37. Blue Fox

38. Haugen platinum

39. Blue star

40. Tundra

41. Lapponia and shadow lapponia as pups

42. Shadow (shadow white)

A Russian dark type of blue fox, the tundra fox (picture 40) is also produced on some farms in Scandinavia.

43. Polar fox

44. Polar fox as pup

45. Arctic pearl

46. Sapphire (Swedish)

47. Oppdal sapphire (Norwegian)

48.Polar sapphire

The most common restive mutants of blue fox are the Swedish sapphire (picture 43). The Norwegian Oppdal sapphire (picture 47) is proved to be allele to the Swedish sapphire. Other recessive types are pale blue type, arctic blue and the beige brown arctic pearl (picture 45).

The polar type is grey in the summer and as small pups (picture 44) but white in winter. Even in winter it usually can be distinguished from white shadow by bluish grey shade on the bottom of the underfur (picture 43)

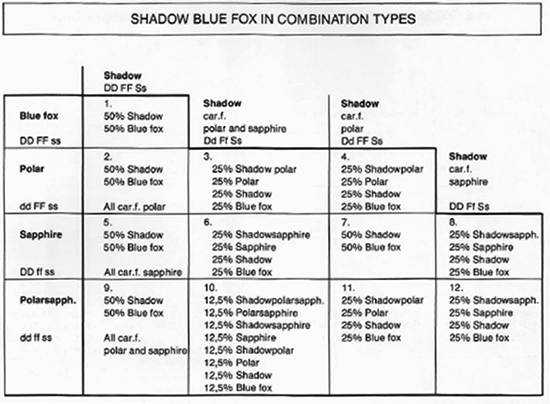

Table 12

When mating polar or sapphire to normal blue fox, only blue fox is produced in the first generation. In spite of the blue fox phenotype they are, however, carriers for either polar or sapphire. The results in further breeding with these are presented in Table 12. Here again the table only gives the segregation of different phenotypes (pelt colors). The genotypes can in most cases be figured out as described earlier. For example the blue colored cubs from a mating polar x sapphire are all carriers for both polar and sapphire. By mating these double heterozygous individuals together it is possible to get a new double recessive type, polar sapphire. Directly after birth these pups resemble the sapphire but later on the color begins to change like in the polar cubs (picture 48). In the winter coat the polar color dominates over sapphire and the polar sapphire is white like polar fox.

Table 13

Shadow is the most common mutant color on our blue fox farms. It is caused by one of the many allelic forms of s-gene. In the same series of alleles are known e.g. blue star/jotun (picture 39) and Haugen platinum (picture 38). They are all dominant and include a lethal factor. Matings between these types must therefore be avoided.

This applies also to either dominant mutant type, Lapponia. Lapponia is a mutant where the distinction from normal blue fox is perfectly clear on small cubs (picture 41) but becomes much slighter in adult animals on the winter pelage. Lapponia and shadow genes are in different chromosomes and can therefore be combined in the same individual. The shadow factor is, however, stronger and in the winter pelage covers the lapponia color. As small cubs these double dominants can, however, be distinguished from both lapponia and shadow cubs (picture 41).

The dominant genes shadow, jotun/blue star and lapponia can also be combined with any of the recessive types. In these combinations it is advisable to use reasonably dark shades of the respective mutants. Of these combinations the shadow polar is specially interesting in interspecies crossings. Shadow polar mated with standard silver, gold fox or red fox produces 50% golden island (picture 52) and 50% golden island shadow (picture 55).

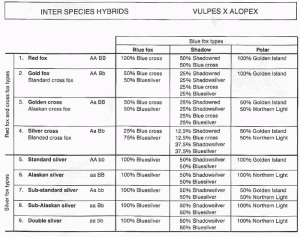

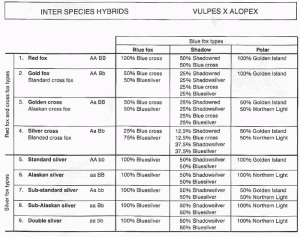

Table 14

The crossings between different silver fox and blue fox types are today an important part of our pelt production. These matings can , however, only be used to produce pelts, because the offspring are sterile.

Within one species the inheritance of color genes follows the Mendel’s laws of heredity. The same laws apply even in inter-species crossings, but as our knowledge about the location of color genes not yet extends to the chromosome level, it is impossible to predict which genres from these two species will form a pair of genes in the inter-species bastards.

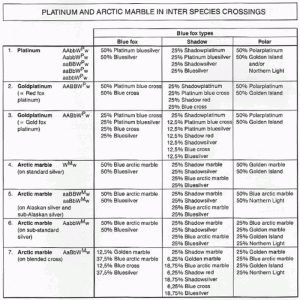

Judging by the interspecies types already known, we can draw some conclusions. the dominant factors, which in the own species cause a pattern (e.g. platinum, arctic marble and shadow) have the same effect also in inter-species bastards (pictures 50, 57-60). Of these combinations the shadow silver is usually darker than a combination of platinum silver fox and shadow blue fox gives some almost white cubs, which have inherited both shadow and platinum genes. Arctic marble combined with blue fox resembles the genuine arctic marble (picture 60) and can only be distinguished by the hair type.

The color of offspring from matin silver fox x polar fox depends on the genetic type of the silver fox in the same way as in cross fox production. Standard silver fox gives the red type golden island (picture 52) and Alaskan Silver fox the more grayish type northern light (picture 54). In the type called golden island shadow (picture 55) both shadow and polar genes are present. Red fox x polar fox gives a similar result as the standard silver. However, the red color appears already on the pups and is on the winter pelage even more prominent than in the offspring after standard silver.

49. Bluesilver

So far we have little experience about the recessive mutants in these combinations. An interesting one is, however, the blue type dawn sapphire in picture 53. The type resembles the silver fox sapphire. It can be produced by mating any silver type including the pearl factor to the Swedish sapphire blue fox. An easy way of producing beautiful blue skins.

51. Golden island and northern light as pups

52. Golden island (in October)

53. Dawn sapphire

54. Northern light

55. Golden island shadow

A standard silver type of arctic marble mated with polar will produce 50% of pups resembling sun glow, in Table 16 referred as golden marble. The other half of the offspring will be golden island.

If the Arctic marble is of Alaskan type, we get instead of golden island a northern light type and the arctic pelts will be more like cross fox marble or blue arctic marble.

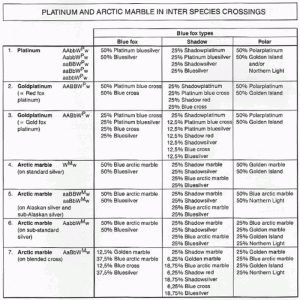

Table 16

56. Blue fox mother and platinum bluesilver pup

57. Platinum bluesilver (pups in August)

58. Polarplatinum

59. Shadow red (pups in August)

60. Blue arctic marble

Danish Fur Breeders Association. Mutant Color Phases of Fox, Mating Combinations for Practice, 1985. Danish Fur Breeders Association.

Books

Books